On Tour With the Blue Notes: A Sights and Sounds 2018 Diary

November 5, 2018

Day 1, Thursday.

11:55 a.m. Goen Hall, Columbus

We’ve loaded the bus. Some people have too many carry-ons. It’s cold and hot at the same time. Those who are just now getting on the bus are having trouble making a complete Venn diagram of available seats and people to sit by that they don’t completely despise. Everyone is praying that the luggage in Ms. Barham’s van stays still; we don’t want to spend four days wearing the same clothing.

As I’m typing this, 12:05 passes, then ten past. We were supposed to be leaving campus by noon.

This is a band trip. This is beautiful.

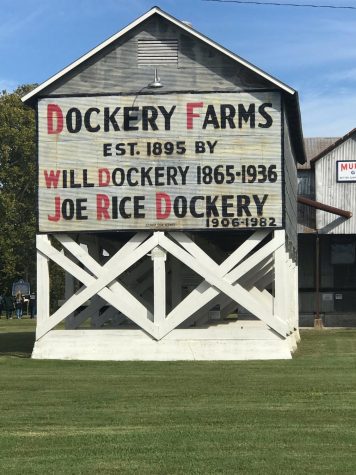

The group visted Dockery Farms in Cleveland, Mississippi.

Sights and Sounds is an event started ten years ago by Ms. Barham as a showcase of music at MSMS and as a learning opportunity for the music program. Each year the MSMS Blue Notes, that is, the band and choir, take a tour of our state. Each year the course of the tour alternates between North Mississippi (our destination this year) and South Mississippi. Along the way, the group performs at various schools and musically significant locations. The setlist is all songs written or performed with ties to Mississippi.

This year, 49 students are traveling to eight cities, five museums/historical sites, and four performances in two states. We are joined by Ms. Barham, our director, Julie Heintz, a social studies teacher at MSMS, and “Mama” Ruth and Ms. Keisha, res-life staff members.

(Forewarning: This is not intended to represent the experiences of every student who participates in the tour. I’m also a percussionist, so make of that what you will.)

1:50 p.m. Pilot Travel Center, Winona

Strange connections can be revealed on band trips. We just stopped at the Pilot Travel Center/Gas Station/Truck Stop in Winona. Stops at gas stations are almost guaranteed at some point on any trip longer than 50 miles. It’s a chance to use the bathroom and indulge in some deliciously unhealthy food. The reason I bring up this specific gas station is that I’ve been here before; multiple times, in fact, and apparently a number of my bandmates have been, too. Even Julian Martin, a junior saxophone player from Booneville, in the Northeast, has a story about this gas station. I suppose it has something to do with location. Winona is located at a somewhat important junction on I-55 for a number of west Mississippians. Band trips run through here often, as do baseball tournaments. It’s also the place where a number of new MSMS students from the west leave the familiarity of I-55 for the first time towards Columbus in the east by way of HWY 82.

2:10 Highway 82, outside Greenwood

Mama Ruth just asked Ms. Keisha, who’s driving the bus, “Are we there yet?”

2:46 The Emmett Till Marker, Money

Our first stop is the Mississippi Freedom Trail Marker at Bryant’s Grocery. The Grocery is overgrown and boarded up, the second floor is missing, and the storefront is long since torn down. There is a NO TRESPASSING sign, and I’m not sure if it’s for the Bryants’ sake or for the sake of Emmett Till, who was lynched close to here in 1955 by Roy Bryant and Bryant’s half-brother J.W. Milam after Bryant’s wife Carolyn lied to them that Till had flirted with her in the store while spending the summer at a relative’s farm. When his body was taken from the Tallahatchie River three days later, he had a broken leg, both wrists broken, and a bullet in his head. His mother insisted on a public, open-casket funeral at their home, Chicago; the funeral attracted tens of thousands, and images of Till’s body were spread across the world, bringing awareness to the amount of work that still needed to be done to mend the scars of racism and slavery in the South.

Once again, Till was murdered because Carolyn, a white store owner who was 21 at the time, lied about Till, a 14-year-old black kid, flirting with her. This occurred 90 years after the end of the civil war. Roy Bryant and Milam were acquitted by an all-white jury. Carolyn was never brought to trial. Over fifty years later the marker commemorating the site is still the victim of racially directed vandalism.

3:15, Robert Johnson’s Grave, Greenwood

Gateway to the Blues – Tunica, Mississippi

Our next stop is the grave site of Robert Johnson (1911-1938) in Greenwood. Robert Johnson was a blues singer, guitar player, and songwriter who was rumored to have sold his soul to the devil in exchange for otherworldly talent. He was described as being able to sound like two voice and two guitars at once. His mastery of the Delta Blues style with influences from all realms of contemporary music brought him two years of fame before an untimely death at 27. Very few true details about his life are known; official records from his life contain conflicting information, and there are only two verified photos of him in existence. Also, the Blue Notes are performing his song “Sweet Home Chicago.” On the grave there are a number of guitar picks, a few flowers and empty alcohol containers, and a Chinese coin. People from all over the world make pilgrimages to Mississippi because of the music born here.

4:17, B.B. King Museum and Delta Interpretive Center, Indianola

Our first museum of the tour begins with a film detailing the origins of the late world famous Mississippi bluesman. It has old videos of his performances, interviews with him, his bandmates, local figures in Mississippi and Eric Clapton, and narration that points out that King’s recording history is over 40 hours long back-to-back.

From there, it proceeds like many other museums, with walls covered in images overlaid with quotes and facts relating to the Delta, King’s life, and the track of his career, which spanned from Church Street in Indianola, to Beale Street in Memphis, and on to touring the world. Various memorabilia that represent 20th century life in Mississippi and blues as much as they do King himself are on display. King’s grave, much fancier and better planed than the others we’ve seen so far, sits outside, and a number of us pay our respects.

5:20 The Courtyard Blues Bar and Grill, Indianola

Practically down the street from the museum is the location of our first gig, a restaurant owned by Kiera Monroe’s family. Kiera (AKA Keke) is a senior member of the Blue Notes choir. However, after the sudden departure of a band member a mere two weeks before tour, she was asked to take over trumpet solos on “Sweet Home Chicago” and “Boom Boom.” Her family offered us a venue and a place to eat dinner, so of course Ms. Barham accepted.

Before we can go inside and order, however, we have to set up, what Barham refers to as “getting the elephant/monster/tour on its feet.” Across a narrow street from the restaurant is a lot with a wrought-iron fence and a rudimentary wooden stage. The walls of the adjoining buildings have large-scale portraits of blues greats paints We’ve had brief experience with getting our set-up done at a previous performance, but now we have more equipment to keep track of and less space to put it. To our credit, a large number of us were responsible for this back home, and we get done in a timely fashion. My job consists of three commands:

- Set up percussion equipment. I’m not sure it’s possible to have too much experience with this, given the second command.

- Guide my section members through setting up. One would think that folks with years of performing on a particular instrument would know the ins and outs of putting things together where they need to be, but one would be wrong. The seniors who have done this before definitely know, but the truth is that not all music programs in the state of Mississippi are created equal, and some parts of music education are lacking in some places, including getting a show on the road. This is particularly evident in former drumline members, who rarely have to put together an instrument stand.

- Keep folks away from our instruments. This is one that is primarily imposed by myself. I know that when people, including other band members, see percussion instruments, their first instinct is to bang on them. Not only is that a risk for the instruments, but it degrades our professionalism as percussionists when we let it happen.

Dinner is good, but we take too long to order and eat and miss our performance time of 7:30. By the time eight o’clock rolls around, we still haven’t played a single note. This is normal for a school band, being laughably behind schedule. It keeps our level of spontaneity up.

We start playing at roughly 8:15, starting with “Boom Boom,” an instrumental piece because some choir members are still eating. Past that, the performance is admittedly not the best; multiple soloists forget parts and/or lyrics, microphones are not used effectively, and a neighboring building is playing music way too loud, overpowering our sound for the meager crowd we’ve gathered. However, Barham didn’t want to play at any venues that would charge admission; she’s received enough complaints from parents from parents tired of paywalls.

When we finally get done playing at around nine, it is so dark and cold that the lights illuminating the stage may as well be the divine light of God in their brightness and warmth. Then we have to pack up, possibly the only thing more frustrating than setting up. Everyone and everything are in each others’ way, as the trailer containing our equipment has to be packed in a very specific order to ensure that nothing breaks and that the thing can close. In addition, everyone has their phones flashing everywhere in a double-edged attempt to mitigate the darkness. We can see what we’re doing, for sure, but at any moment one is apt to be blinded by a misplaced beam.

We get on the bus to travel to our hotel, having expected to leave by nine, and my roomate, Austin Eubank, asks me for the time. I look down. Nine fifty.

Roughly 10:45, Econolodge, Greenville

It’s way too late and the day has been way too long to notice much about our hotel rooms other than the fact that somehow the power outlets are connected to the light switch. However, I do at least notice that we are in Greenville, which is a somewhat (in)famous place when it comes to marching bands. Every year I’ve been around bands I’ve seen them at state evaluations. They are one of a shrinking group of bands that still march in the traditional style. Their drum major brandishes a baton, their steps are all high-steps, and majorettes dance on the front sideline to the pop tunes the band is playing behind them. While they never score very well, they are a refreshing turn away from modern marching shows, which tend to be impressive while also occasionally soulless.

Day 2, Friday

6:00 a.m. Econolodge, Greenville

Waking up is not a very fun experience when most of what you have to look back on and forward to is hours of riding the bus.

6:57 a.m.

I have done something I’m not completely proud of. I’ve eaten Froot Loops with apple juice because no milk was available and because Barham is determined to at least leave the hotel on time.

7:57 a.m. Ruleville High School, Ruleville

We’ve stopped in front of the location of our second performance, Ruleville High School, and a few minutes earliiiiii…where are we going?

8:03 a.m. Ruleville High School, Ruleville

Unfortunately, a lack of communication has resulted in us spending valuable set-up time driving in a slow circle around the school back to where we stopped in the first place instead.

Ruleville High School/Elementary School gym, where the principal is Keke’s mother! (It pays to have connections in music.)

Gyms typically present an acoustical challenge for musicians because reverberations are killer. Any whisper or shuffling of feet or anything of that sort is amplified and becomes highly distracting. Also, low-pitched sounds tend to drown out higher ones, so percussionists on drumset have to be especially careful that we don’t go whole hog on the kick, or else the entire band’s sound becomes meaningless noise. Even the sound check we do as our audience files into the gym sounds horrendous. Our audience, by the way, is mainly elementary schoolers, with a few members of the high school band.

Audiences of young children are sort of a mixed blessing. On the one hand, they are easily impressed, and will cheer on anything, while on the other hand, they typically don’t know what common courtesies are expected of them as audience members, such as not talking over the performance. Both qualities are on high display as we get going. Thankfully the only people who notice me accidentally throwing a drumstick during “Book Boom” are the trumpet players struck by it.

When we are done with our set, Barham brings forward Sophia Garcia, Jessikah Morton, and Kiera, who all came to MSMS from Ruleville, to receive a round of applause from the audience. As this is going on, Camryn Mason, in charge of loading the trailer, starts a timer.

Without waiting for the applause to stop, we start breaking down our equipment and taking it outside to the trailer. I even ask Amyria Kimble, a member of the choir who was on drumline back in Horn Lake, to help dismantle some cymbals.

Some of the members of the MSMS Step Team show off for the kids. We continue loading. At this point our vocabulary for communicating for each other in which order instruments are loaded into the trailer contains five different meanings for the phrase “That goes in last.”

We shut the trailer. The timer stops. We’ve finished in less than ten minutes, which would be a miracle even if we didn’t have three dozen instruments to keep track of. I check my phone. It’s 10:13. Somehow we manage to leave the school 45 minutes ahead of schedule.

10:32 a.m. Dockery Farms, Ruleville

If Mississippi is the birthplace of the Blues, then Dockery Farms is the front porch the baby came out on. Dockery Farms (it’s really a plantation, but the name hasn’t lasted in today’s aversion to such terms) is where Charley Patton grew up and developed the foundation of all of American music while working in the fields. He was known for finding creative ways of playing his guitar, such as behind his back and on top of his head. Robert Johnson looked up to him as a child.

The reason that many Delta musicians got their start working on plantations is that the plantation owners knew that if they kept popular musicians around, it would be easier to keep other workers content with the near-slavery situations they were trapped in. As a result, musicians would often get better paying and easier jobs on the plantation.

As Barham is explaining the closed-circle nature of a plantation economy to us, one of the members of the Dockery family who still lives on the site pulls up in his truck.

“Across there used to be where Charley Patton house was, and a bridge used to span this gap here,” he says, gesturing across a small valley filled with water and kudzu. “A lot of people think that the old musicians only played in juke joints on Saturday nights, but that building wasn’t a juke joint. It was Charley Patton’s house. The farmers would pay him to move all the furniture out of his house. Then, they would bring in these huge mirrors and hang them up all over the house. When the sun went down, they would light a bunch of oil lamps everywhere, and this is before electric lights, and no one else had much more than a little lamp that would get extinguished after dinner, so on Saturday night from a mile away it looked like Charley Patton’s house was on fire with all the mirrors everywhere. Then they would charge 25 cents to cross the bridge to get to the house, and they would make so much just from admission that Patton was making a couple hundred bucks himself on Saturday nights. He eventually made so much that he could buy a new car every week if he wanted to.”

He also tells the story of Robert Johnson not selling his soul to the devil before he bids us farewell. After a brief tour of the cotton gin and a picnic on the grass, we take a group photo in front of the plantation’s iconic sign painted on its front, then pack up and leave.

1:03 p.m. Hopson Commissary, Clarksdale

We pull into another former plantation. It’s been explained to us that the commissary used to contain the plantation’s post office, barber’s shop, doctor’s office, bar, and, if you went to the back, the “club.” Nowadays the commissary is still a bar, and there’s still a pole in the backmost room, but the backyard has been converted to a small concert venue, and sharecroppers no longer need the post office. The sharecroppers’ former houses, in fact, have been converted to a hotel known as the “Shack-Up Inn.”

Hopson was another plantation that attracted sharecroppers with the promise of good music. Joe “Pinetop” Perkins was a pianist for Muddy Waters’ band, and had a successful solo career of his own, but he also worked at Hopson for a decent portion of his life. Why? Forgive the terrible pun, but he had a nearly-captive audience that would pay him well over a week’s salary every Saturday night, and had a much easier job than others (if you can call any job on a farm in the 40’s easy.) In fact, Perkins was one of the first people in the world to drive an International Harvester. Every year, from the time he left the Delta in the 50’s until his death in 2011, Perkins would make a homecoming trip to Hopson, and the music festival he started is still held on the anniversary of his homecoming.

At about 1:45, we depart for Memphis.

2:58 p.m. Robinsonville Outlet Mall, Tunica Resorts

We’ve entered the region known as the “Midsouth.” Tunica Resorts (AKA Robinsonville) is a town slowly dying in every aspect except for its nine casinos. The outlet mall we’ve stopped at for gas used to have no empty shops; now 4/5 of them are without tenants. In a hyperbolic sense, the only people who live here are farmers and casino workers. On the close horizon is the Gold Strike Casino Resort, the tallest building in the north half of Mississippi. In a few minutes we’ll be driving past my home school, Lake Cormorant, which was built in the middle of a cotton field. On a clear morning, you can see Gold Strike from the front steps of Lake Cormorant Elementary, twelve miles away, which is probably only a reassuring sight if one (or both) of your parents work at the casinos.

3:58 p.m. The Heart of Downtown Memphis, Tennessee

This is the town where Martin Luther King Jr. was killed. Fedex is headquartered here. The best zoo in the nation and the best barbeque in the nation are both here. A giant glass pyramid overlooks the Mississippi river here just as the Gateway Arch does in St. Louis.

Memphis was and is the goal, or at least an important step, for many Mississippi musicians, including, but not limited to, B.B. King, Elvis Presley, Muddy Waters, Rae Sremmurd, Big Walter Horton, and Conway Twitty, and is also the home of Justin Timberlake. Beale Street is where legends are born. We’re standing a block away not from the birthplace of the blues, but certainly the place they were raised.

We are walking into another museum.

Don’t get me wrong; I love the potential for museums as places for the preservation and appreciation of culture and history, but after being rushed through so many of them to fit a preordained schedule, the museums on this trip have become a blur of famous guitars and stage outfits. Our current location, the Rock and Soul Museum, at least has an accompanying audio tour, but we leave before seeing half of what the museum has to offer.

4:28 p.m. Fedex Forum/Beale Street, Memphis

I tend to consider Downtown Memphis as a relatively safe place, compared to other cities. I mean, most of the best music is gone from the street, either to the grave or to the recording studio, but that also means that some of the grit that gave Beale Street its reputation is gone.

“When looking at violent crimes, Memphis, TN has 188% higher violent crime rate than Tennessee average, while remaining 371% higher than the national average.”

-www.areavibes.com

“The ratio of number of residents in Memphis to the number of sex offenders is 301 to 1.”

-www.city-data.com

“MY CHANCES OF BECOMING A VICTIM OF A VIOLENT CRIME:

1 IN 55 IN MEMPHIS”

(On a scale of 1-100, with 100 being the safest) “Memphis Crime Index: 1”

-www.neighborhoodscout.com

We are instructed to walk in groups of no less than four people.

We’ve got three hours to explore the street end to end. The only traffic on Beale Street is foot traffic. I suppose at some point people figured out that blocking it off and not having cars driving through the city’s biggest tourist attraction would be a good idea. It has another museum that we’re allowed to go into (yay), a few shops that we’re allowed to go into and a few dozen bars that we’re most definitely not allowed to go into. Some of the attractions on Beale street are Silky O’Sullivan’s, with their “beer-drinking goats,” B.B. King’s Blues Club and the Beale Street Flippers, a group of acrobatic street performers.

My subconscious screams as the group of students I’m tethered to walks right past the live music in the clubs and into the Withers Collection Museum and Gallery, which I’m going to describe as: more stage costumes and guitars. I sneak out of a side exit and into another group heading back down the street.

5:10 p.m.

We stop by A. Schwab’s, a souvenir shop and the only remaining original business of Beale Street, and buy some gelato.

Suddenly, in the distance:

Boom-Boom-dut-dut-dut, Boom-Boom-dut-diddle-iddle-iddle, Boom-Boom-dut-dut-dut, Boom-chicka-Boom-Boom-GOCK-GOCK-GOCKGOCK!!!

I presume that simultaneously, the ears of Austin, Amyria, Nathaniel Lee, Mia Parker, Advaith Sunil and myself, all percussionists, perk up at the sound, and alarms go off in our heads. If they aren’t headed there already, we drag our groups outside, where we find a drumline set up in the middle of the street. The Grizzline has arrived on Beale.

The Grizzline, founded in 2006, is a professional drumline for the Memphis Grizzlies NBA team. It is composed of a rotating group of 15-20 percussionists from around the Midsouth that performs during the pregame, halftime, and timeouts. Their sets are high-energy original compositions that incorporate, to a large extent, the individual personalities of the performers.

Today they’ve decided to make an appearance of Beale Street, completely uncoordinated with our arrival at the same location. People dance. One man holding a pair of drumsticks who doesn’t appear to have had any formal (or informal) musical training bangs them on the ground off-beat and out-of-time and completely blissful. Some of the Blue Notes are visibly fangirling, as much about the line’s technique as about the quality of the performance, and I would be lying if I say I’m not doing this internally as well.

The snares are jumping around, playing each other’s drums. The tenors are incorporating more pelvic thrusting into their performance than I believe I’ve ever seen in any performance, both in out of the context of a drumline. The basses are at least keeping the beat (it is difficult, to say the least, to be flashy on bass line.)

The majority of the group leaves to look around some more, but a few of us stay for the entire thirty-minute performance and then follow the line over to the plaza in front of Fedex Forum, where the Grizzlies will play tonight. Right now, however, the line starts up yet another long performance, seemingly without repeating a single song. I’m definitely impressed with their endurance, how they can drum for so long while maintaining tempo, running around, and giving a performance.

After they finish playing, some of the percussionists give some Blue Notes some of their sticks. Some of the choir students believe that their sticks have been autographed by the people using them, and this is where a gap in knowledge is noticeable. While there are signatures printed on these sticks, the sticks were made with these on them, the names those of the people who designed the stick, something that the percussionists in the Blue Notes point out to the people who aren’t content with being excited about getting a used drumstick.

We hang out a bit on Beale, and it’s seven thirty before we know it. We eat a modest barbeque dinner in a private room above the Blues City Cafe before walking back to the bus under a light drizzle of rain, and drive back to Tunica.

9:34 p.m. Highway 61 outside Lake Cormorant

As we pass Lake Cormorant, I look out the window to see if I can’t catch a glimpse of some Friday Night Lights, but check my schedule and see that the LC Gators are playing the Olive Branch Conquistadors in Olive Branch. Mama Ruth is acting delirious from being tired and is singing “The Wheels on the Bus,” greatly annoying Ms. Keisha.

10:16 p.m. Microtel Inn, Tunica Resorts

I have no idea why Barham picked the Microtel in Tunica for us to stay at. Perhaps this was the cheapest option, but the only thing I know is that this is far removed from anything resembling civilization (unless you count the casino a third of a mile away.) At least the power outlets work here. I’m too worn out from the events of the day to do much of anything tonight but sleep, so sleep I will.

Day 3, Saturday

Unfortunately, a family emergency in DeSoto County takes me away from the tour on Saturday morning. While everyone else goes to the Gateway to the Blues Museum in Tunica, I’m at Baptist Memorial Hospital in Southaven.

Fortunately, no one is dead, and the hospital is down the road from the next performance venue.

11:15 a.m. Minor Memorial Methodist Church, Walls

The closest connection that Minor Memorial has to music history is that Elvis Presley’s ranch is a couple hundred yards away. Fifty one years ago, when Elvis bought the property, Desoto County had a sixth of the population it has today, and the intersection of Goodman Road and Highway 301 where the ranch stands wasn’t nearly as traveled. The ranch was bought on a whim, and served as a place where Elvis could get away from his life as a superstar, but nowadays would be completely unrecognizable to the King. Once, he lost his wedding band somewhere in the field. To this day, no one has found it; not many people pay much attention to the ranch, especially people like me who drive by it on a regular basis. There were plans unveiled recently to turn the land into a tourist site like Graceland, but most locals approach these plans with heavy skepticism.

Meanwhile, the church I meet the Blue Notes at is hosting a fall festival outside. An Elvis impersonator, likely unaware of the site a stone’s throw away, is performing when I walk over to meet back up with the group. Some people have gone through the festival and bought various items, like rubber band guns or yo-yos. I run into one of my close friend’s mothers. He isn’t here because the Lake Cormorant band is at a marching competition in Memphis.

12:00 p.m.

Setting up here is a bit different than at the other locations so far, in that we aren’t the only performing group of the event. We can’t immediately put all of our equipment in the staging area, because Elvis is standing there. Instead, everything gets put together off to the side and around the performing area. When those before us finish and move out of the way, we will move everything into the vacated space and get our sound systems set up before performing. While this is happening, I imagine the Lake Cormorant Marching Band doing more or less the same thing, and I silently wish I could be with them.

12:30 p.m.

Elvis says his last “thank you very much”, tells the crowd that he’s available for events, and cedes the stage to a three-man cover band from Nebraska that’s missing its percussionist. Their bassist plays the cajon in their place.

1:00 p.m.

The group from Nebraska ends their set. We promptly take at least 15 minutes setting up, taking extra time because the sound system is on the fritz, and having to adjust the balance of volumes of the different microphones because we are outside isn’t helping. Nevertheless, everything is set up, and the band begins to play.

As we were getting ready to perform, a number of our families arrived; Desoto County, the largest school district in the state, predictably sends a large amount of students to MSMS. Playing for a home crowd is typically considered easy, but sometimes can add pressure to show out in front of one’s biggest fans. Even then, it’s a special experience, considering we’ve been gone at school for the majority of the past three months.

When we are finished playing, and people have had a chance to talk to their families and take advantage of some free food given to us by the church, we begin setting up to perform again inside the sanctuary in the morning. Playing as the featured music of tomorrow’s service is scheduled as our last performance of the tour, but I wouldn’t mind another eight performances. (The statements made in this article have been made by one person, and do not necessarily reflect the views of any of his peers.)

Departure commences, though I notice that in my absence the seating arrangement of the bus has shifted to take advantage of the empty space near the front of the bus.

4:55 p.m. Strike Zone Bowling Lanes, Southaven

This spot on our itinerary read “Plans TBA” up until now, primarily as a function of Barham taking this long to make a decision on where we were going to go. I and a few others hoped we might be going to the aforementioned marching competition, but bowling is bowling. We have fun for a couple hours arguing about playing with or without bumpers, putting seven songs into the jukebox at once and being in each others’ company. The scores of the games don’t really matter outside of the ones I win.

8:20 Microtel Inn, Tunica Resorts

Half the fun in band trips comes from performing and going to different places. The other half comes from being on buses and in hotel rooms. The conversations that occur are somewhat like those typically shared during study hours at MSMS, by which I mean that they have nothing to do with anything of any importance, except to those having them. I am heavily considering including some things I have overheard in this account, but am deciding not to in order to not betray the trust of multiple friends. What happens on a band trip (that doesn’t break any rules or the Geneva Conventions) stays on a band trip. Sleep, however, does not elude me, but instead clubs me over the head at around midnight.

Day 4, Sunday

11:31 a.m. Minor Memorial Methodist Church, Walls

Our final performance of the tour is over. We left the hotel at nine dressed in our Sunday best, the chilly morning certainly more of a nuisance for those of us wearing dresses than those of us wearing coats. Barham had already let us know that if anyone had any objections to attending the service, they could remain outside the room until our performance. Our set was only the more religiously oriented of the songs we took on tour both because we didn’t have an hour to perform and because we didn’t want to burst into flames playing the song “Natural Woman” in the middle of a church service.

The church has offered us lunch, and a common trend should be noticed that we tend to take up people’s offers of food. I call up a friend who lives nearby to join us. He and I talk for a minute about our bands before we both have to leave, and I realize that both of us have become used to the fact of my not being at Lake Cormorant. A miniscule portion of me leaves and rides home with my friend.

We begin the drive home.

3:50 p.m. Goen Hall, Columbus

Back on campus at last. The return from a typical band trip happens after midnight in a school parking lot, and everyone falls asleep on the ride home with their parents. I suppose it should be fairly obvious that MSMS is different in this regard. Instead of sleeping, we all start on homework that’s accumulated from missing a day and a half of school. It’s almost impossible to not be busy at MSMS.