Reece: Parchman, a prison in peril

Parchman has yet to correct its racial history and continues to be evidence of systematic disenfranchisement of African Americans within the prison system.

January 16, 2020

Nestled between the fields and crops that decorate the Mississippi Delta rests an infamous house of horror that has become a blemish on Mississippi and America’s prison-industrial complex as a whole.

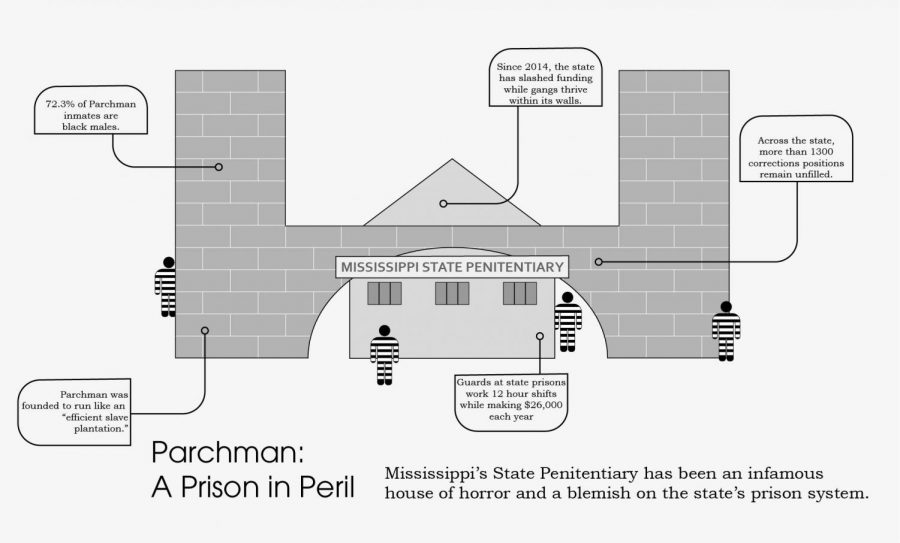

Mississippi State Penitentiary, also known as Parchman Farm, is the state’s only maximum-security prison for men. Burrowed into various parts of Sunflower County in 1901, Parchman was built on the back of healthy black inmates who tended to the field and constructed their own hell. While white prisoners were sent off to Rankin Farm and female prisoners going to Oakley Farm, Parchman was reserved for black males, who, according to then Mississippi governor James Vardaman, “run(s) ‘like an efficient slave plantation’ that provided young black men with the ‘proper discipline, strong work habits, and respect for white authority.’”

The Clarion-Ledger claims that “In a system that resembled slavery, inmates labored on the plantation and worked other dangerous jobs for free for 10 hours a day, six days a week and slept in buildings called “cages,” all the while making a profit for the state.”

Parchman has yet to correct its racial history and continues to be evidence of systematic disenfranchisement of African Americans within the prison system. In 2008, 72.3% of inmates within Parchman were black males, who already make up the largest portion of the national prison population.

As if this harrowed history of racism was not enough, Parchman also became infamous during the Civil Rights era, with Freedom Riders tossed behind the deadly cinder block walls. According to Complex, “the Freedom Riders were subject to strip searches, disgusting food, and constant psychological abuse.”

Since then, Parchman has shown little humanity and growing concerns for the civil liberties of prisoners. Numerous lawsuits spanning decades have brought allegations of racism and police misconduct to the prison, but thanks to a recent storm that disrupted cell phone jammers intended to keep prisoners from accessing cellular services, new problems from within the farm have come to light.

According to Photography is Not a Crime (PINAC) News, a not-for-profit news agency specializing in government accountability, “a prisoner recorded showing a fire lit within prison walls. The prisoner says other prisoners created multiple fires to get the warden’s attention, as one of the prisoners was in desperate need of insulin and in the middle of having a diabetic attack.”

As one prisoner puts it, “We in this [expletive], man we got a brother down in this. You know what I’m saying? He ain’t have his insulin. He sick bro. We been in this building with no power. The warden just came and put the first fire out… they don’t give a [expletive].”

Another prisoner claims he was shot by the guards in connection with lighting the fires, saying he was “Laying on the floor, man, on the lower part of my back so you know I couldn’t be doing nothing man. I was shot in the lower part of my back. I was laying down when they shot me man.”

Even before the onset of the storm that knocked power out at the prison, Parchman inmates were complaining about a lack of power, running water and rat infestation since June. Reports have also surfaced claiming that due to a lack of funding from the state and corruption among the prison staff, gangs from within the prison have took it upon themselves to administer Parchman. According to CBS News, “At least one lawsuit alleges ‘barbaric’ conditions at the prison, including rats, open sewage, abusive guards and corruption. Yet since 2014, Mississippi has slashed funding and staffing, and gangs like the Vice Lords and Black Gangster Disciples have thrived inside.”

Gang culture within Parchman dictates where inmates rest their head at night to what they eat and how much they get to eat. Some guards appear to be either ambivalent to the happenings within the prison or complacent in the violence. Just in the last two weeks, five prisoners across the state of Mississippi have been violently mauled, three at Parchman.

Mississippi Governor Phil Bryant, who yielded his seat to Tate Reeves earlier this week, blamed the riots on gang culture while neglecting to mention the fact that funding for the prison has been cut for years in favor of large tax cuts.

For the guards that are not shooting their inmates or neglecting appearance medical emergencies, they are still working 12-hour shifts and dealing with massive understaffing and abysmal underpayment. According to CBS, “But almost half of the roughly 1,300 corrections positions in three major facilities in Mississippi remain unfilled. Even with a degree, guards start around $26,000, which is around the national poverty level for a family of four.”

Parchman is yet another example of a dark system that disenfranchises prisoners and tramples over their civil liberties. While it is important to recognize that these inmates were found guilty of a crime and must legally be punished according to said crime, it is immoral to believe that those individuals still do not deserve basic human decency and should not have their inalienable human rights tossed aside. No one in sound moral compass can look to Parchman and see it as a humane system that is working properly. Parchman’s prison system, Mississippi’s prison system, and America’s prison system do not work. Parchman still revels in the ramifications of institutionalized racism and work must be done to properly fund and rebuild our prison system as a whole. A society should be judged on how it treats the lowest among them, and when scholars and historians look onto to Parchman prison in the future, they will see nothing but death, corruption, and an inherently inhumane system destroying the lives of citizens.

When famed American Delta Blues musician Bukka White produced his song “Parchman Farm” in 1940, he uttered lines that prove even more consequential today:

“Oh listen you men, I don’t mean no harm

If you wanna do good, you better stay off ol’ Parchman farm.”

Margaret Maugenest • Jan 17, 2020 at 7:30 pm

Thank you for shining a light on Parchman. I had no idea. This is heartbreaking.