Movie Review: Experiencing “The Room”

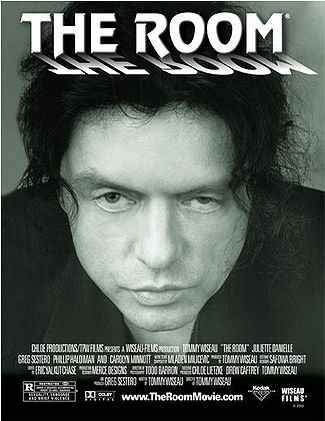

Theatrical release poster

December 4, 2017

“The Room” (2003), directed by, written by, and starring the mysterious Tommy Wiseau, has garnered much infamy since its premiere, where it earned an impressive $1,900 at the box office. Greg Seresto, one of the actors and producer of “The Room,” revealed in his 2013 memoir, “The Disaster Artist,” the difficulties during production and Wiseau’s many idiosyncrasies, including his peculiar prejudice against the French and tendency to forget lines he wrote himself. Not much is known about Wiseau, not even his birthday, though with his lank black hair, pallid face, and ambiguous European accent, he’s probably a vampire.

Seresto’s memoir has since been adapted into an acclaimed film of the same name produced by James Franco and first screened at South by Southwest earlier in 2017. “The Disaster Artist” had a limited premiere last Friday and will have a widespread premiere this Friday, Dec. 8. I recently grew interested in the original film “The Room,” given the buzz surrounding the release of “The Disaster Artist” and what I had heard about it in the past.

Optimists consider “The Room” a “so-bad-it’s good” type of film, like rating a movie is a circle-based scale, not a linear one, and “The Room” has come through the opposite direction. Seeing out-of-context quotes from the film around the internet like “Oh, hii Mark,” has done nothing to illuminate me on the film’s content. But after watching the movie, I don’t think I feel much more in-context.

Johnny, portrayed by Wiseau himself, is apparently a father figure to a random highschooler named Denny. Johnny’s fiancée or “future wife” (because fiancée is French) is named Lisa and portrayed by Juliette Danielle. Greg Seresto portrays Mark, Johnny’s best friend and the object of Lisa’s affair. If you have never heard of these people, I am not surprised.

The Room gets down to business rapidement. The introduction is an indulgent softcore fantasy of Wiseau’s, composed of slow panning shots hinting at things I cannot describe here. These scenes demonstrate an abundance of soft lighting, roses, candles, and funky music. But suggesting “The Room” has any form of coherent thought in its cinematography is very generous.

Johnny is allegedly a successful banker, which is why Lisa’s mother pushes her to stay with the man, though Lisa has fallen out of love with him. Lisa must have whiplash from how fast she’s switched men: one scene she’s crawling on Johnny, and the next she’s vilifying him, looking to seduce Mark instead, who has the spine of a worm. Lisa cites Johnny’s failure to get a promotion, his drunkenness, and his hitting her as reasons against him. Johnny does have a drinking problem, quite like Ted Striker in the movie “Airplane!” (1980), where he can’t have a glass of whiskey without it dribbling all over his chin. I can’t quite recall if Johnny actually does hit Lisa, but I do know Johnny says “I did naht hit her, I did naaht.” Regardless, while these seem reasons enough for resentment, since none of the characters are capable of effective communication, a resolution lies beyond their comprehension.

“The Room” has the same complexity of dialogue to be found in an introductory foreign language textbook. Its plot is as compelling as a foreign language textbook’s story, and conflict materializes from tension as tangible as mist. The acting is questionable, though I think most actors tried their best given the limply constructed material. Tommy Wiseau has a range of intonation as varied and interesting as a kiddie coaster. Seresto seems like he’s just along for the ride. Juliette Danielle’s character Lisa is like a caricature of a woman. Denny is disturbing and useless, and the other minor characters are moral advice robots. The characters harbor little logic and can’t even tell in a glance that a person lying very still and covered in blood is probably dead.

“The Room” boils down the complexity of relationships until it carbonizes on the pot. It’s an absurd creation born out of Wiseau’s hopefully-not-personal experience, though it is evident in what is probably Wiseau’s best acting in the whole film, he seems to channel some deep inner resentments. “The Room” ends on a cliché note, though honestly entirely appropriate.

What baffles me is how so many people came to support such a strange project, though that’s likely what motivated its rise to cult status in the first place. Recognition through cult status, and most recently “The Disaster Artist,” brings “The Room” some legitimacy or maybe notoriety. Its infamy certainly does much to serve Wiseau’s ego. Watching “The Room” is a surreal experience involving peering into the mind of a bizarre man with very particular opinions about the world. I am at least glad to say I have experienced a staple of terrible cinema. If you choose to watch “The Room,” I hope you will, too.