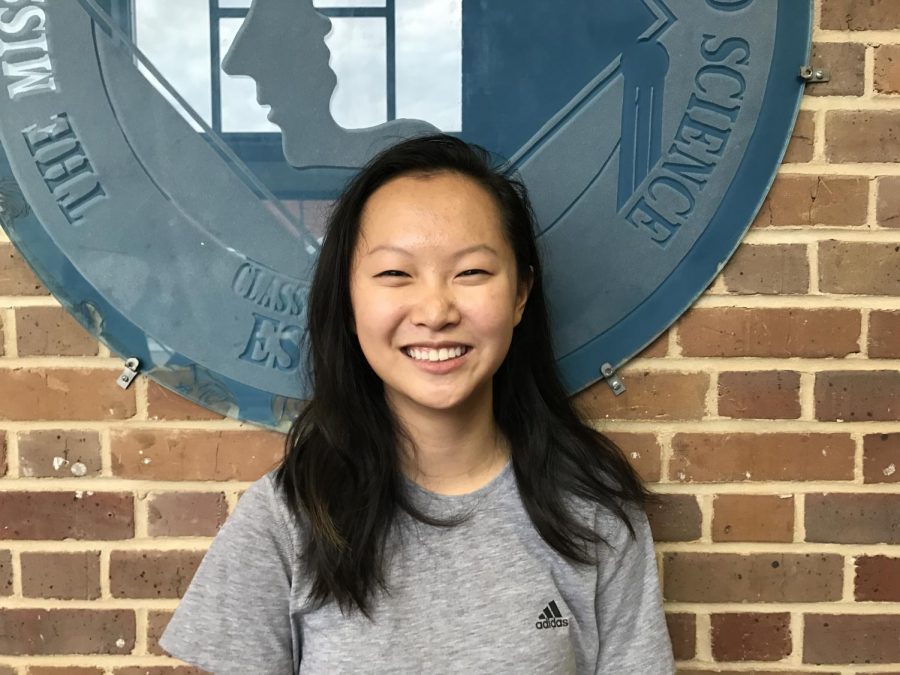

Peng: “Crazy Rich Asians” and Child-Rearing

September 17, 2018

“Crazy Rich Asians” premiered in theaters August 17 to frenzied crowds of eager waters, featuring one of the few of Hollywood’s all-Asian casts. Despite the 93% on Rotten Tomatoes, critics deem it stereotypical of Asian culture- from Rachel Chu’s economics major to Nick Young’s rich and overbearing family. Granted, some Asian stereotypes in this film are overplayed, but given the under-representation of Asians in the entertainment industry, “Crazy Rich Asians” broke boundaries and highlighted important and often unseen truths in Asian culture and tradition.

“Crazy Rich Asians” follows economic professor Rachel Chu’s journey in meeting her boyfriend, Nick Young’s, horrifying family and tells of Chu’s discovery of the truth of her past as well as her reaction to the truth of her boyfriend’s family. Behind Nick’s normal New York glamour, Nick’s family is the ‘it’ family of Singapore. He’s got thousands of fangirls smitten with him and hundreds of years of family tradition to uphold. To avoid giving too many spoilers, I’ll jump to my topic of argument: the antagonization of Nick’s oppressive, controlling and family-oriented parents. Eleanor Sung-Young, Nick’s mother, disapproves of Rachel Chu due to socio-economic status and attempts to ward her away at the expense of her son’s happiness. Her motive is clear: happiness is an illusion, and family tradition comes before all.

From the perspective of Asian children, Mama Young’s harsh exterior isn’t unfamiliar. I wasn’t necessarily raised to think that “happiness is an illusion,” but the controlling nature of parenting was present. To “Western” kids, Mama Young’s character may seem like an “evil step-mother,” yet in reality she is only a dedicated mother who, perhaps, takes too much responsibility for ensuring her child a comfortable future. Although the harsh villain that Mama Young formed may indeed be interpreted as cold-hearted, from a tiger-family’s standpoint there is only love.

Take “Battle Hymn of a Tiger Mother,” for example. Amy Chua’s method of child-rearing is questionable to most. Chua’s determination for her children to achieve success may seem over the top, even questionable and borderline abusive. To outsiders Chua is a cold dictator living through her puppet children and the end justify the means as they both turn out successful. When “Battle Hymn” was released, there was confused backlash paired with various interviews to clarify that Chua wasn’t an abusive being. Sure, Asian parenting may not necessarily foster the warm and easy-loving support that other families care to show, but love is instead shown through actions and the assumptions that the hardships enduring will be worth it later. “Crazy Rich Asians” follows a similar, though less serious, parallel. Both offer a popular insight into the commonly misunderstood aspects of Asian culture.

Whether or not these stereotypes are exaggerated or not, they are still a step towards an understanding of an ethnicity and culture commonly misunderstood.