Leise: School Class Officer Elections

November 12, 2018

By the time the modern cotton gin was invented by Eli Whitney in 1793, the technology necessary to create it had been available for centuries. It was, in actuality, so simple of a concept than Whitney struggled to obtain a patent for it. Ten days after being tasked to devise a more efficient method of removing cotton seeds from the boll, he had a working prototype.

Why did it take humanity so long to develop this marvel of simple machinery?

We were content with the status quo. We spent centuries separating cotton by hand for hours on end because we figured, “Why bother making this easier?”

They were wrong.

High school class officer elections are of far, far less consequence than the cotton industry in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, of course. For example, at MSMS the primary duties of junior class president, vice-president, secretary, historian, and treasurer are to plan Prom in the spring. However, that doesn’t mean that the process has to be left in a potentially flawed state, lest we run ourselves into the same mindset of accepting pointless inefficiency, as cotton farmers did so many years ago.

My main grievance is with how a significant number of schools, MSMS included, handle the elections of their presidents and vice-presidents.

With the current method that MSMS uses to determine these positions, potential candidates for spots as class officers have the choice of either running for president or vice-president. I believe that those who want to run for either position should run collectively for class president, and the candidates receiving the most and second-most votes should win president and vice-president, respectively. There are a few reasons for this.

First, a class vice-president should be qualified enough to be class president (define “qualified” how you will). Part of a vice-president’s duties are to perform the duties of the president when they are unavailable. Therefore, a vice-president ought to have the capability to be president, if need be. Allowing someone to run for vice-president who may not be comfortable running for president is like trusting Schrödinger’s Cat to keep vermin out of one’s pantry.

Secondly, a number of candidates for class vice-president under the current system may run for that office because they feel that, based on the pool of other candidates for president, they have a better chance of winning vice-president. Too often have I heard classmates, running for positions similar to vice-president, say that they do so only because of beliefs somewhere along the lines of, “So-and-so is more popular than me, so they’re probably going to win anyway.”

Those people aren’t unjustified; that is the kind of situation that separate elections for president and vice-president create, but this doesn’t have to be the case. Having one election for both positions would allow candidate to focus on what’s really important, like finding ways to carry out on their campaign promises to have an ice sculpture in the image of the “Norton Anthology of American Literature” at Prom.

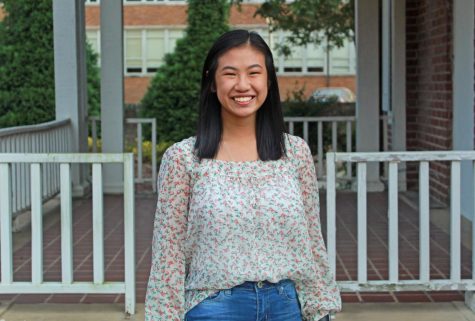

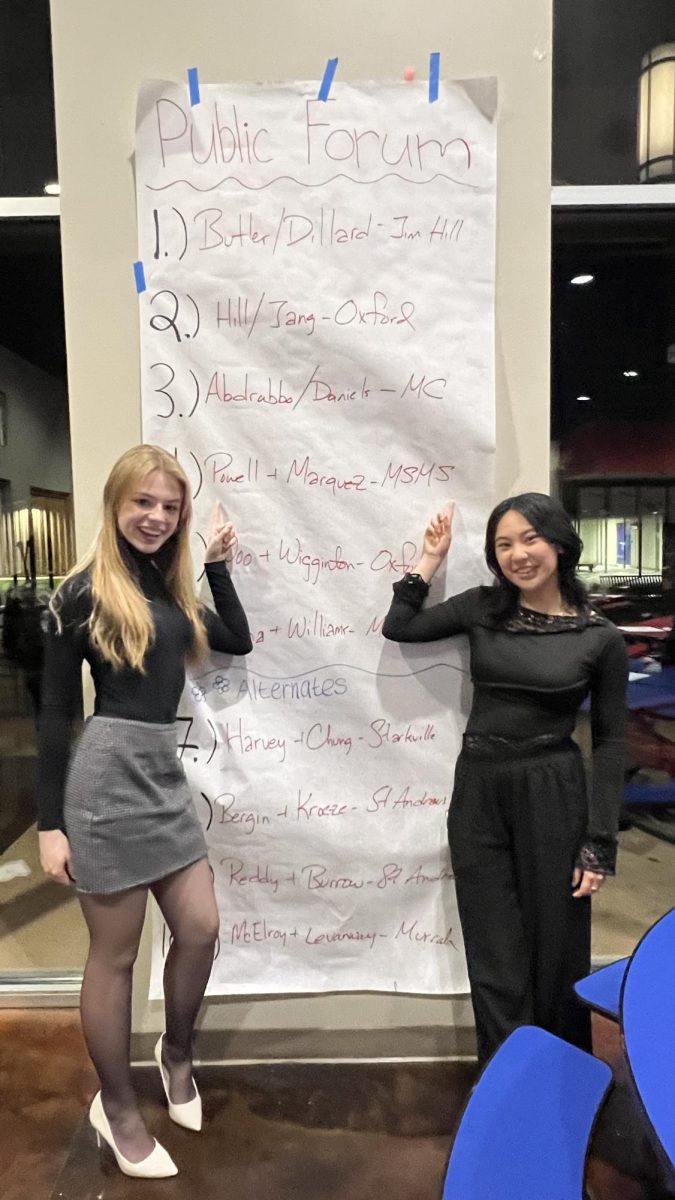

Thirdly, fewer offices to directly elect means fewer votes to count, making elections more efficient. The election for junior class vice-president of 2019 at MSMS went through several rounds of runoff elections before Gina Nguyen finally beat-out Christian Fulcher. This situation could have been avoided and less work required of those running the election had there not been an election for vice-president to begin with.

In disseminating these opinions around the time of class officer elections this year, I was met by another possible solution: running mates, similar to the United States presidential election.

For a time, the United States presidential election functioned much in the way of my proposal, namely the top two vote-earners winning president and vice-president, until the third presidential election in 1796. In that election, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, candidates from separate parties, received top votes, with Adams winning the Presidency. The conflicts between them during their time in office were so severe that the Twelfth Amendment was added to the constitution, separating the elections for president and vice-president, much like school elections are run nowadays. This system continued until candidates realized it was more advantageous to campaign together, and eventually states simply printed running mates together on voting ballots.

The reasons following this example wouldn’t work for a school election are that

- Class officers at schools do not run on the platforms of political parties and are not endorsed by them.

- The issues faced by most school governments aren’t severe enough that having those in office with differing viewpoints wouldn’t halt progress. Instead, it could lead to better representation of the student body overall.

- Some people might not be able to find running mates.

While the outcomes of what are likely more popularity contests than anything else do not drastically impact the course of a student’s life, we at least owe it to future classes to make sure they are fair. Let us not be like our ancestors, separating cotton from its seed by hand, one boll at a time. Instead, I hope we can continue to find simple solutions to the status quo.